Antarctica? Almostica. When planning a trip to Antarctica, one expects to actually get there. Ah, the best laid plans of mice and men....

We decided a trip to Antarctica needed to get on our radar. Fantastic photos of ice, penguins, mountains, and the ocean proved too intriguing to ignore. Yes, the trip would be expensive. What value, though, can you place on seeing such a special environment assaulted from so many directions by modernity? Add to that the smug achievement earned by adding another stamp to our passports and being able to say, “Yeah. I’ve been to Antarctica.” It had to happen. We worked closely with Lori Snow of Condor Tours and Travel to book our group with HX, Hurtigruten Explorations’ Antarctic voyage on February 11, 2025. HX operates the Fridtjof Nansen, a 459-foot luxurious 490-passenger capacity ship in numerous expedition locations, including waters between the southernmost tip of South America and the Antarctic Peninsula. To ensure their passengers have the best experience, Hurtigruten limits the passenger load on its Antarctica voyages to 390 people, thereby minimizing their impact on Antarctica’s delicate ecology.

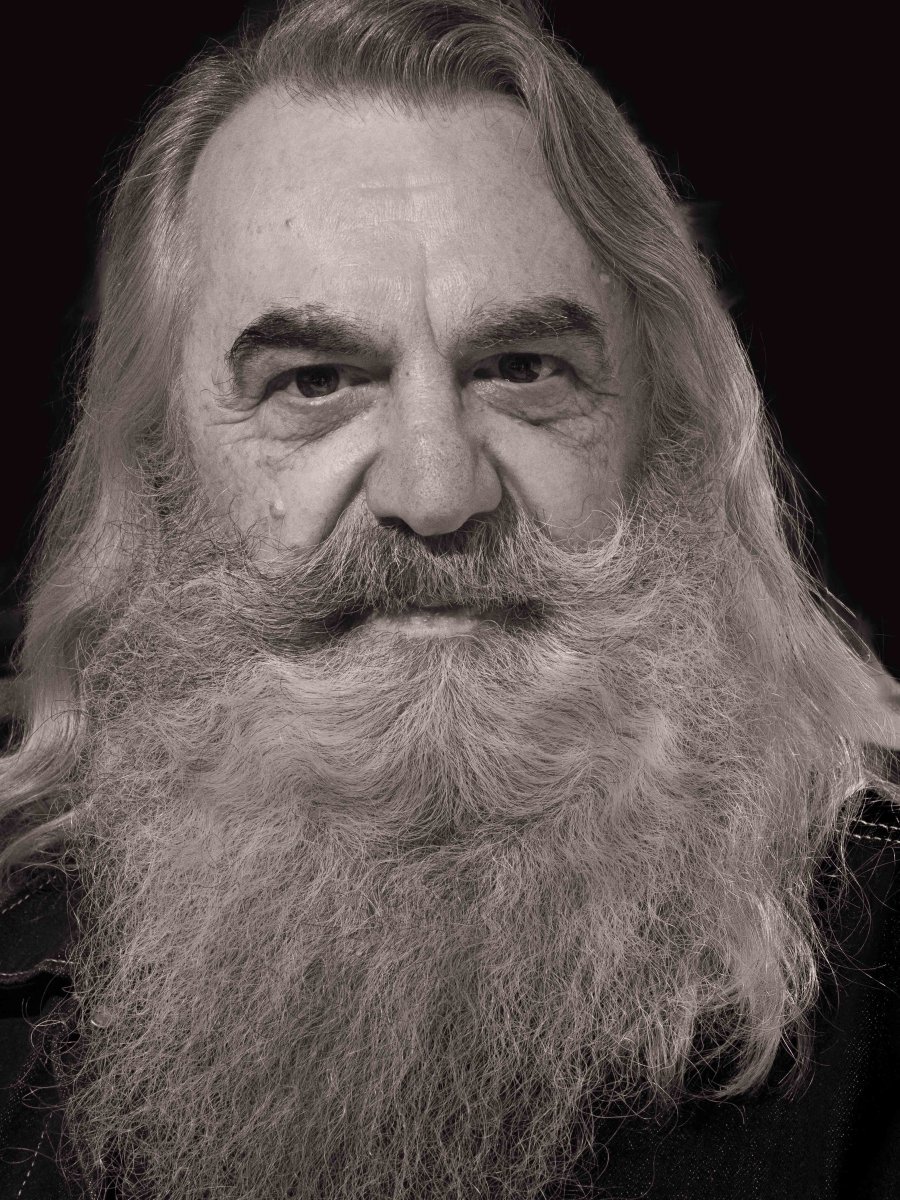

We invited friends from our regular photo travel group and secured agreements from Anthea Letsou, Jim Metherall, and Janis Weiss. Anthea and Janis took my photography classes at the University of Utah. Jim provides adult supervision for Anthea. My wife, Shielia Nash, and I completed our group of 5 adventurous photo enthusiasts. Off to Argentina we went.

Trips to Antarctica typically involve a stay in Buenos Aires followed by an air leg to Ushuaia, Argentina’s southern tip, a short 600+ mile sail across the Drake Passage. From Ushuaia, explorers land on the Antarctic Peninsula, extending northward from Earth’s southernmost continent. Ships land explorers on the peninsula, saving time, lots of money, and avoiding potential weather issues if landing further south. Commercial trips to Antarctica take place during the Antarctic summer, the northern hemisphere’s winter, keeping travel conditions and weather more tolerable for armchair explorers.

With all that said, our Buenos Aires portion worked out well as we spent our first February days enjoying summer during the heart of winter in Salt Lake City. Shorts and T-shirt weather in February seemed out of place as we enjoyed guided tours from Valeria Oleszkiewicz around Buenos Aires and environs. We found no shortage of great scenes and people to photograph.

With all that said, our Buenos Aires portion worked out well as we spent our first February days enjoying summer during the heart of winter in Salt Lake City. Shorts and T-shirt weather in February seemed out of place as we enjoyed guided tours from Valeria Oleszkiewicz around Buenos Aires and environs. We found no shortage of great scenes and people to photograph.

Buenos Aires is a large modern metropolitan city. Valeria guided us to famous locations such as the Recoleta Cemetery, the final resting place of Eva Peron. We witnessed the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, a gathering in front of the former presidential palace every Thursday at 3:30 PM since 1977. There, they call attention to their missing friends and loved ones, disappeared from their families and friends without a trace many years ago.

Buenos Aires is a large modern metropolitan city. Valeria guided us to famous locations such as the Recoleta Cemetery, the final resting place of Eva Peron. We witnessed the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, a gathering in front of the former presidential palace every Thursday at 3:30 PM since 1977. There, they call attention to their missing friends and loved ones, disappeared from their families and friends without a trace many years ago.

On a more artistic note, we visited Rancho Susana, a ranch demonstrating Argentina’s Gaucho past and agricultural lifestyle.  Although

Although situated on a completely different continent, with a different culture and geography, this part of Argentina bears a strong resemblance to my childhood home in Central New York. Following the horse-drawn wagon property tour and an authentic Argentine lunch, we witnessed one of Argentina’s major exports: Tango dancing. It seems Argentines are very proud of this dance heritage. We saw them at Susana Ranch, on street corners, and at the famous MichelAngelo’s dinner theater in downtown Buenos Aires.

situated on a completely different continent, with a different culture and geography, this part of Argentina bears a strong resemblance to my childhood home in Central New York. Following the horse-drawn wagon property tour and an authentic Argentine lunch, we witnessed one of Argentina’s major exports: Tango dancing. It seems Argentines are very proud of this dance heritage. We saw them at Susana Ranch, on street corners, and at the famous MichelAngelo’s dinner theater in downtown Buenos Aires.

Gleaming in its metallic glory, we loved photographing Eduardo Catalano’s brilliant Floralis Generical sculpture. Wracked by high winds during a December ’23 storm, it no longer opens and closes, imitating a natural flower, but still graces the Plaza de las Naciones Unidas Park, making a fantastic photography subject. Buenos Aires offers a plethora of photography subjects, such as the above shown remnant from the early Argentine Navy. Its people and culture make great subjects. But we were there to go to Antarctica.

Gleaming in its metallic glory, we loved photographing Eduardo Catalano’s brilliant Floralis Generical sculpture. Wracked by high winds during a December ’23 storm, it no longer opens and closes, imitating a natural flower, but still graces the Plaza de las Naciones Unidas Park, making a fantastic photography subject. Buenos Aires offers a plethora of photography subjects, such as the above shown remnant from the early Argentine Navy. Its people and culture make great subjects. But we were there to go to Antarctica.

Our 3:45 A.M. rising to catch our bus transportation to Buenos Aires Ezeiza airport for our 7:00 A.M. Ushuaia flight went smoothly, as several hundred passengers made their way from the Buenos Aires Hilton to our nearly 1,500-mile flight. The Jet Smart charter service presented us with pre-packaged picnic food on their utilitarian, bare-bones flight for the next 4 hours, while we listened to a fellow passenger behind us hack and wheeze the entire flight. Fine. A person spreading a respiratory virus is just what we need to begin our Antarctic adventure.

Hurtigruten gathered us at the Ushuaia airport, divided us into groups, and sent ours on our way into the Ushuaia countryside via chartered buses. I’m sure they needed to

Hurtigruten gathered us at the Ushuaia airport, divided us into groups, and sent ours on our way into the Ushuaia countryside via chartered buses. I’m sure they needed to split us up so nearly 400 confused and anxious passengers weren’t lined up attempting to board our ship at the same time. While I would have preferred taking a nap aboard ship in our cabin that afternoon, we found the mountain landscape around Ushuaia quite scenic. It turns out producers filmed several scenes of the movie, “The Revenant,” near Ushuaia when their originally planned filming locations didn’t work out. Hurtigruten provided a tasty lunch buffet

split us up so nearly 400 confused and anxious passengers weren’t lined up attempting to board our ship at the same time. While I would have preferred taking a nap aboard ship in our cabin that afternoon, we found the mountain landscape around Ushuaia quite scenic. It turns out producers filmed several scenes of the movie, “The Revenant,” near Ushuaia when their originally planned filming locations didn’t work out. Hurtigruten provided a tasty lunch buffet  at the Haruen Winter Center outside the city. I was surprised to see chairlift towers near there. It turns out that competitive skiers from around the world go to Ushuaia in the Northern Hemisphere summer for off-season training. We met Alfred Tozzi in his small Haruen gift shop. He reportedly made a historic trip aboard his Enfield motorcycle from Alaska to Ushuaia. His small shop featured old motorcycles, books, maps, and some of his self-brewed gin. We finished lunch, reboarded our bus, and headed to the harbor to meet our ship.

at the Haruen Winter Center outside the city. I was surprised to see chairlift towers near there. It turns out that competitive skiers from around the world go to Ushuaia in the Northern Hemisphere summer for off-season training. We met Alfred Tozzi in his small Haruen gift shop. He reportedly made a historic trip aboard his Enfield motorcycle from Alaska to Ushuaia. His small shop featured old motorcycles, books, maps, and some of his self-brewed gin. We finished lunch, reboarded our bus, and headed to the harbor to meet our ship.

Unloading from our bus at Fridtjof Nansen’s port side along the Ushuaia dock, we secured our luggage, ascended the boarding gangway, sent our carry-ons and suitcases through a metal detector, and faced what I called the board of inquiry. That sounds a lot like Hurtigruten’s crew intimidated us, but it was far more friendly than it looked. They verified our paid passage and IDs, sending us to our shipboard homes for the next 10 days.

After unpacking and squaring ourselves away, several of us made our way up to the Fridtjof Nansen’s “fast food”  restaurant, where we grabbed a burger and slaked our hunger. After that, it was mostly time to hang out with a few delicious beverages while awaiting our cast-off and departure. Finally, about 9:00 PM and 2 hours late, we felt a few vibrations and looked out Deck 10’s lounge windows to see the dock slowly receding, our wake expanding, and the Ushuaia’s mountains fading. A short time later, we made our way to our cabins for the night.

restaurant, where we grabbed a burger and slaked our hunger. After that, it was mostly time to hang out with a few delicious beverages while awaiting our cast-off and departure. Finally, about 9:00 PM and 2 hours late, we felt a few vibrations and looked out Deck 10’s lounge windows to see the dock slowly receding, our wake expanding, and the Ushuaia’s mountains fading. A short time later, we made our way to our cabins for the night.

Educating ourselves on the ship’s rules, regulations, and schedule, we took our place in the following morning’s breakfast lines at the handwashing stations outside the dining room. Hurtigruten’s crew adamantly enforced handwashing procedures. As it later turned out, the execution and efficacy of passenger handwashing differed dramatically. The day slowly unfolded with exceptional educational presentations, HX water bottle artful decorating, more eating, and some deck walks. I did a bit of photography around the ship as we made our way through the South Atlantic. I couldn’t help comparing the view from our sleek, modern, and comfortable ship with images brought to mind by reading of Earnest Shackleton’s ill-fated Antarctic expedition at the turn of the 20th century. We were warm, dry, well-fed, and rested as I watched cold, wind-whipped wavetops blow by, indifferent to our passing. The day drifted into the afternoon, followed by another leisurely night and early to bed turn-in.

The following day repeated the previous. We felt fortunate for the rolling long waves outside our windows. We had yet to encounter any Drake Shake, though our long rolls made their impression on my internal balance. I was starting to feel a little seasick, but I felt I could tough it out. About mid-afternoon, the ship’s PA system announced our captain would like passengers and crew to gather in the deck 10 lounge for an announcement. I figured we’d get introduced to our ship’s staff and learn how grateful our crew felt for us making this voyage with them.

Gathering more than 300 people together took a little time. Our little group sat together as the captain began to speak. He told us we had a sick passenger aboard who suffered from life-threatening disease symptoms. The captain, crew, and ship doctor determined they needed to turn the ship around and sail back to Ushuaia so they could deliver our sick passenger to hospital facilities there. After a brief hush fell over the audience, our captain and his crew detailed their decisions, describing how & why they decided to turn the ship back to Ushuaia. There was no way to transport the ill passenger directly from the ship’s current location. Since the only available helicopter in the region belonged to the Chilean Navy and was otherwise committed, that option was out. Fridtjof Nansen wasn’t designed for helicopter landings on its deck anyway, which meant a winch transfer for our ill passenger. The weather was also too rough for a helicopter, regardless. I think we had already made our course change by then and were already on our way back to Ushuaia.

Several passengers raised rather intense concerns about the remainder of our trip. They appeared quite upset. What was Hurtigruten’s plan to complete our trip? How were we all to be made whole? Our captain explained we couldn’t return to our original itinerary after delivering our ill passenger to medical care. Strong winds with 10-meter-high waves lurked between us and our return Antarctic course if we attempted. The captain asked for our indulgence and another meeting later that evening. He said they’d have more answers for us and a course of action for the remainder of our itinerary.

Later reconvening, the captain laid out Hurtigruten's offers and options. For those wanting to terminate their sail, Hurtigruten said the company would allow passengers to disembark the ship when we transferred our ill passenger. Hurtigruten would help facilitate passengers’ return home. For those wishing to continue, Fridtjof Nansen would make a course eastward to the Falkland Islands, where we’d tour the port of Stanley on East Falkland Island, followed by stops at several smaller islands to explore wildlife sanctuaries and rookeries. Hurtigruten also offered refunds or credits for any of its other itineraries for those wishing to travel to other destinations on different trips. In addition, to make up for our misfortune and failure to reach Antarctica, Hurtigruten offered to pay for us to be on the same trip during the 2026 season, including airfare at the same flight class. We felt we had nothing to lose in taking the Falklands option. Since we’d likely never visit the Falklands for any other reason, this turned out to be a great opportunity for an unexpected adventure courtesy of Hurtigruten. Our group stayed aboard.

During our westward-bound day and a half return, we spent our downtime leisurely strolling about the ship, reading up on the Falklands, and attending several subject matter expert lectures in the ship’s education center. Many passengers spent time with  Hurtigruten’s team comparing options and making plans for future Hurtigruten Expeditions cruises. When we pulled into Ushuaia, Hurtigruten had arranged with the harbor to have space at the dock where we could meet with medical staff from the local hospital and transfer the ill passenger. As the transfer occurred, we lined the ship’s upper deck railing, passengers craning their necks to see who caused this giant bubble in everyone’s plans. We never got a solid look, but from the descriptions and shipboard rumor mill, our hacking wheezing passenger from the Buenos Aires flight, the guy who sat behind us and to our left, was the culprit. He sounded so awful on the flight, we wondered who bore responsibility at Hurtigruten for letting this person onboard in the first place. It was too late at this point. There was no way to undo it. Bring on the Falklands!

Hurtigruten’s team comparing options and making plans for future Hurtigruten Expeditions cruises. When we pulled into Ushuaia, Hurtigruten had arranged with the harbor to have space at the dock where we could meet with medical staff from the local hospital and transfer the ill passenger. As the transfer occurred, we lined the ship’s upper deck railing, passengers craning their necks to see who caused this giant bubble in everyone’s plans. We never got a solid look, but from the descriptions and shipboard rumor mill, our hacking wheezing passenger from the Buenos Aires flight, the guy who sat behind us and to our left, was the culprit. He sounded so awful on the flight, we wondered who bore responsibility at Hurtigruten for letting this person onboard in the first place. It was too late at this point. There was no way to undo it. Bring on the Falklands!

Fridtjof Nansen’s superior engineering and crew expertise ensured our hold position in the Beagle Channel as the dock was scheduled for other ship traffic. The ship’s computer-controlled GPS positioning and crew expertise safely kept us from harm’s way in the channel as Hurtigruten and the Falkland Island authorities worked out details of our sail in their direction. They ensured Stanley Harbor would have room for us without encumbering any other ships in the area. The next day, we began our eastward journey to East Falkland Island.

As we approached East Falkland and Stanley, the ship began PA announcements stating several passengers were having mild gastrointestinal symptoms, reminding everyone to thoroughly wash hands, especially when entering the dining areas. Ominous. While on East Falkland, we hired a local tour operator to conduct a visit to a small penguin rookery. Once we arrived at the rookery, we, along with dozens of our fellow travelers, hiked a trail to see the rookery occupants. They were few and forlorn -looking. Definitely not worth the effort. I photographed Magellanic Penguins in the wild. More interesting to Anthea and me was the Canache, at the west end of Stanley Harbor, where several historic ships and numerous local sailors docked. Until the advent of the Panama Canal, the Falkland Islands served as a valuable refuge for ships about to attempt, or ships barely surviving, the travails of South America’s Cape Horn transit.

-looking. Definitely not worth the effort. I photographed Magellanic Penguins in the wild. More interesting to Anthea and me was the Canache, at the west end of Stanley Harbor, where several historic ships and numerous local sailors docked. Until the advent of the Panama Canal, the Falkland Islands served as a valuable refuge for ships about to attempt, or ships barely surviving, the travails of South America’s Cape Horn transit.

A great tourist attraction and the lone recognizable hull remaining of the many ships finding Stanley as their final resting place, the Lady  Elizabeth, an iron three-masted barque, limped into Stanley in March of 1913. Declared unseaworthy, Lady Elizabeth served many years as a floating warehouse for cargoes while their ships were under repair. In 1936, a severe storm swept into Stanley, breaking Lady Elizabeth from her moorings and blowing her to her current resting place in Stanley Harbor’s Canache, where wind, weather, and seawater slowly degrade her once-flowing lines. This history was provided online by the Topham Sailing Club and Falklands Marine Heritage Trust.

Elizabeth, an iron three-masted barque, limped into Stanley in March of 1913. Declared unseaworthy, Lady Elizabeth served many years as a floating warehouse for cargoes while their ships were under repair. In 1936, a severe storm swept into Stanley, breaking Lady Elizabeth from her moorings and blowing her to her current resting place in Stanley Harbor’s Canache, where wind, weather, and seawater slowly degrade her once-flowing lines. This history was provided online by the Topham Sailing Club and Falklands Marine Heritage Trust.

Anthea and I walked the 4 miles from the island’s best photo site at the Canache to our departure dock, consuming most of our  afternoon. Our ship was a welcome sight for resting up before dinner and embarkation for West Point Island, the site of our next day’s exploration and photography of bird and penguin rookeries.

afternoon. Our ship was a welcome sight for resting up before dinner and embarkation for West Point Island, the site of our next day’s exploration and photography of bird and penguin rookeries.

The following morning, we approached the launching area for Fridtjof Nansen’s RIB craft used to ferry passengers ashore. The ship’s PA system messaged passengers and crew to gather in their assigned groups and teams to start moving people ashore  on West Point Island. We were told this island featured several Albatross and Penguin rookeries. After a short 15 or so minute boat ride, we’d land and hike over the island’s spine to the southwest side, where we’d have great wildlife viewing and photography opportunities. By the time we left the ship, I was beginning to feel the effects of the “mild gastrointestinal symptoms” experienced by, as the PA system described, a few passengers. Driven by my determination to get better penguin photos than on East Falkland, I tried to ignore my descending stomach upset. The hike was around a mile in length and delivered me to the Black Browed Albatross rookery. I grabbed a few shots and began hiking over to the Rock Hopper Penguin rookery. As we walked well-worn, deep footpaths in the tall grass, my stomach started telling me it was going to unleash everything it had. I absolutely had to get more penguin shots. My camera faithfully recorded the fledgling Rock Hopper penguins and albatross chicks. I

on West Point Island. We were told this island featured several Albatross and Penguin rookeries. After a short 15 or so minute boat ride, we’d land and hike over the island’s spine to the southwest side, where we’d have great wildlife viewing and photography opportunities. By the time we left the ship, I was beginning to feel the effects of the “mild gastrointestinal symptoms” experienced by, as the PA system described, a few passengers. Driven by my determination to get better penguin photos than on East Falkland, I tried to ignore my descending stomach upset. The hike was around a mile in length and delivered me to the Black Browed Albatross rookery. I grabbed a few shots and began hiking over to the Rock Hopper Penguin rookery. As we walked well-worn, deep footpaths in the tall grass, my stomach started telling me it was going to unleash everything it had. I absolutely had to get more penguin shots. My camera faithfully recorded the fledgling Rock Hopper penguins and albatross chicks. I  wasn’t going to make it much further. Looking around, saw a place away from the group where I thought I could surreptitiously drop to all fours and let loose. I dragged myself over there and started dry heaving. Staring at the grass and weeds just a few inches from my face, I thought, “Maybe this won’t be so bad. Maybe it’s just seasickness.” A moment later, nearly the entire Hurtigruten staff descended on me, asking what was wrong. I told them I felt a little seasick, that I was OK. They immediately insisted I take the emergency vehicle back to the RIB and then return to the ship. I was going to argue but realized I had no strength. Agreeing, Shielia and I went to the car and piled in for the ride back to our landing site. I was hoping my stomach wouldn’t subject me to my fellow passengers’ ill feelings if it let loose in the back of the car. We safely made it to the bay, donned our life preservers, and rode the RIB back to the ship, rushing to our cabin as quickly as we could get there.

wasn’t going to make it much further. Looking around, saw a place away from the group where I thought I could surreptitiously drop to all fours and let loose. I dragged myself over there and started dry heaving. Staring at the grass and weeds just a few inches from my face, I thought, “Maybe this won’t be so bad. Maybe it’s just seasickness.” A moment later, nearly the entire Hurtigruten staff descended on me, asking what was wrong. I told them I felt a little seasick, that I was OK. They immediately insisted I take the emergency vehicle back to the RIB and then return to the ship. I was going to argue but realized I had no strength. Agreeing, Shielia and I went to the car and piled in for the ride back to our landing site. I was hoping my stomach wouldn’t subject me to my fellow passengers’ ill feelings if it let loose in the back of the car. We safely made it to the bay, donned our life preservers, and rode the RIB back to the ship, rushing to our cabin as quickly as we could get there.

I thought if I could only lie down for a while, I’d be OK. Not to be. Shielia started exhibiting the same symptoms. After several violent vomiting episodes and ship doctor visits, the ship’s med staff gathered me up and wheeled me to sick bay, where they dripped 2 bags of Ringer’s Lactated Solution into me over the next day. Though quite ill, Shielia could stay in the cabin while her symptoms worked themselves through. My day spent in the sick bay was the day I looked forward to the most in the Falklands. The shore parties visited an Emperor Penguin colony. Dang! I really wanted to return from Antarctica with Emperor Penguin images. They were part of the reasoning for the entire trip. Sad.

After my 24+ hours in sick bay, I felt well enough to go back to the cabin and start navigating the ship again. Shielia’s recovery was a few hours behind mine. Members of our group were wondering what happened to me and looked around the ship to see where I was. They said they saw ship staff changing mattresses from cabins. Apparently, it wasn’t just a few passengers with mild symptoms. The ship never really acknowledged the extent of the issue. They did, though, close the ship’s public restrooms and increased handwashing announcements. They also deployed more of their staff to clean surfaces throughout the spraying and cleaning of handrails, in addition to other public contact points.

The remainder of our voyage went off without major issues. We had only 2 days’ sailing to return to Ushuaia, where we’d spend our final night aboard the ship, transfer to the airport the following morning, and fly from Ushuaia back to Buenos Aires, followed by our flight back to the USA and home. Little did I know, a case of COVID awaited me when we landed in Salt Lake City.

Once home, we quickly followed up with Lori Snow of Condor Tours and Travel to ensure we were locked into the 2026 version of this adventure. Lori had to do some extra footwork and wear out her telephone, making Hurtigruten fulfill their promises for v2.0. We feel much better prepared. We won’t take quite as much clothing. Since we never learned which bug afflicted our fellow passengers and us, we will be aware of hand contact points and do a better job of our handwashing. Hand sanitizer doesn’t work on the suspected culprit, Norovirus, but a little research pointed us in the direction of surgical handwashing wipes with Chlorhexidine that do. We'll see.

Even with all the trauma, I felt Hurtigruten handled our cruise as well as they could. Their staff maintained pleasant demeanors. They were always willing to help. I felt like they kept us informed the entire time, though they could have been more forthcoming regarding the bug’s rampage through the passengers. Would I sail with Hurtigruten again? Yes, without question. In fact, I can hardly wait for our 2026 voyage.